In 1999, in a move that accurately predicted America’s growing addiction to film franchises, Universal Pictures decided to repackage some of their classic horror films as Universal Classic Monsters. Over the intervening years the number of titles has grown, but initially the focus was on the bigger, more recognized classics like Frankenstein, Dracula, The Mummy, The Invisible Man, The Wolf Man, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon series. They even offered Guillermo del Toro the reins in 2007 but he passed up the offer, a decision he now regrets.

These films are considered classics and their title characters are found to be both frightening and engaging. Frightening because they’re monsters, engaging because they are – for the most part – victims of circumstance:

> Frankenstein was a mad scientist, but Karloff’s monster was an innocent brute whose big crime was not understanding the difference in buoyancy between little girls and flowers

> Dracula may have been evil as a human but now he is a cursed soul, living in ruins like some undead Nora Desmond. The only joys left to him are the rare visit from realtors and the fact that his and his wives’ laundry is always supernaturally clean

> the Mummy is much like Dracula, rich and evil in life but physically hobbled and without means as the undead, hopelessly lusting after women centuries younger than himself and cursed with a weird accent

> the Wolf Man couldn’t help it, he got bit by a wolf, always a good plot device, from vampires to Spiderman. 100% victim. Has there ever been a sadder and less-evil monster than Lon Chaney, Jr.’s, and whose condition caused so much personal anguish?

> the Creature from the Black Lagoon was just another species – in this case, a horny fish man – displaced by humans. We may call him a monster but he sees us as trespassers, and which came first?

BUT

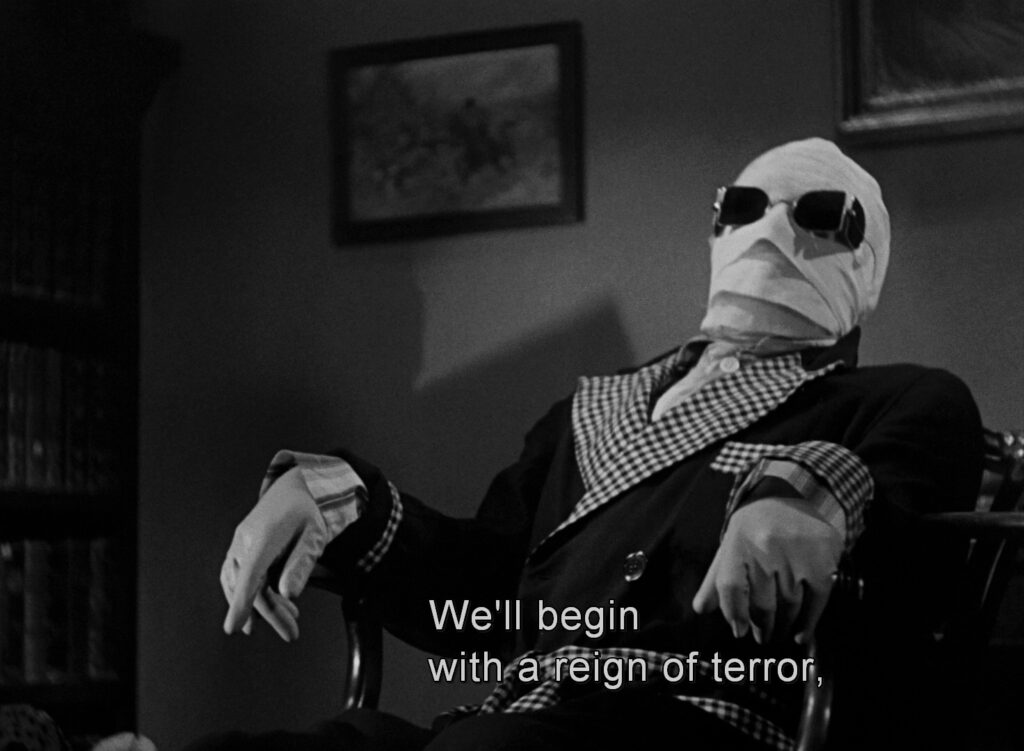

> the Invisible Man was the most monstrous of all, a victim of his own ego and the insidious side effects of monocaine. He was angry as hell, channeling Dr. Jekyll and Marlene Dietrich, just wanting to conduct his drug experiments in peace and losing all control and composure when circumstances change for the worse. There is no external force making him the victim, he drives himself insane through his obsessive drive to fame and power. A scientist who does work that goes down a dark path of mania and drug abuse is another solid film trope, from Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde (another Universal film from 1931) to the various iterations of The Fly as well as this character, but I believe Claude Rains did it best.

I would suggest that his performance is the strongest of the bunch, not the the least because he is limited to his voice and physical mannerisms, his face covered by bandages until the last minute of the film. When he reveals to his girl Flora (actress Gloria Stuart, best remembered as Old Rose from Titanic) that his motivation was the shame of being a broke-ass chemist, it adds a poignant, Breaking Bad sympathetic note, a brief but perfect glimpse into the vulnerabilities beneath the madness. His rants and mutterings are precise and pointed and that dialogue has held up remarkably well over the last ninety years. The fact that he is a bright and educated American who has difficulty making ends meet and develops a nasty and debilitating drug habit is sadly still a contemporary tale.

James Whale’s direction is also of great significance here. The film has much in common with Frankenstein, which he had just recently directed in 1931. In that iconic adaptation, Colin Clive’s manic, mad Dr. Frankenstein diatribes seem much more stagey, grand gestures meant to play to the back of the house, whereas Rain’s Jack Griffin draws us in and infects us with the subversive appeal of his anger and desire to profit from destruction. Even though the film include a series of set pieces that look lifted from a stage production, it’s those moments wherein Whale takes advantage of the intimacy of celluloid with his close-ups and rants at conversational volume that we are most affected by Rain’s acting.

With nary a grand set to romp about in, no haunted castles, no foggy forests, and a script that puts the onus on the main character’s skills to engage us, Whale bet the house on the still unknown Claude Rains, and therein lies the genius of this film. I say genius because the character of Jack Griffith is truly bad and kind of a badass with almost no likable characteristics, and yet I find myself sympathizing with him the entire film. With the restraints placed on him by playing a bandaged character, Rains leans into his vocal and physical deliveries. The shorter run times of these older films (71 minutes in this case) also help prevent character fatigue, but it’s Rains skill and presence that lift this film up to the next level. There are also two facts about the script also bear uncommon influence on the film: first the fact that R.C. Sheriff’s adaptation had to be approved by still-living author H.G. Wells, and that Preston Sturges added his light touch without credit.

How big a monster is this Invisible Man, you ask? One of the more striking details of the plot is that he kills 122 people, starting with a cop. The rest of the body count includes the violent murders of twenty men from the search party, his peer and competitor for Flora’s hand, Dr. Arthur Kemp, and a hundred (!) people in a train he derails over a mountain pass. John Wick is a church deacon writing his weekly sermon in comparison. I was particularly impressed that this was a post-Code film because even though crime doesn’t pay it certainly has a field day. I’ve read more than one review that found Rain’s performance humorous but I find that hard to square with his astronomical and unrepentant kill count, no matter how gleefully execeuted (to be fair, I did laugh when he threw a couple of searchers off a cliff, but that was laughing with him, not at him) and it’s hard not to delight in any dialogue touched by Preston Sturges.

I grew up adoring these monster films on television and still find a familiar comfort watching them today. Many details, large and small, jump out at me now that passed unnoticed before: from the overall glory and wonder of Bela Lugosi’s version of Dracula, or the common underlying tropes recycled plotwise, to the radiant beauty of Elsa Lanchester, it’s Claude Rains performance as the Invisible Man that reigns highest in my regards, from his first appearance in a snowstorm near Iping, through his various costume changes and undressings, to his sudden and brutal death and his deathbed return to his sympathetic human form. Though his body was invisible in the film, his larger-than-life performance will live on.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.