If you’re like me, you like to eat a variety of foods. A new restaurant opens in the neighborhood? I’m in! When one loves to eat it’s easy to get excited by the choices almost every meal. If you only eat domestic fare, your selections are obviously less than if you embraced a wider and more worldly menu. The same goes for film. The hungrier you are for good stories told well on the big screen, the further afield you will forage for them. Just as one might come to prefer Italian or French or Japanese food after a few tastings, so might one be attracted to the films from those countries.

There is, however, one problem often expressed by those who don’t enjoy “foreign” (aka non-native language) films: the subtitles. The reason for this relutance – besides the fact that many people just don’t care and are otherwise lazy AF – is the distraction of focusing on the small area of text instead of enjoying the entire frame. In lieu of actually learning another language, this is a necessary compromise. My only suggestion would be that if you really love a foreign film, watch it again with the subs off. Even if you thought you knew it well, I’d bet there will be some detail(s) you’ll pick up in this viewing to make it worthwhile.

This is why dubbed versions are also available; however, my experience is that the translation for the dub is shoddier than the text one but, more importantly, it’s not the actor’s voice. Director Ang Lee once stated that the voice is sixty percent of the performance. For those that think dubbing is suitable, might I suggest a thought experiment wherein one imagines a film with Morgan Freeman, or James Earl Jones’ Darth Vader, being shown abroad but with another actor’s voice. It will not be the same. I would consider dubs only useful for animated features (where you can sometimes get multiple versions with respectively stellar voice actors, like Persepolis or the Studio Ghibli films), campy movies, or illiterates.

Korean director Bong Joon-ho has strong feelings on this topic. I think many Korean directors feel like they were forced to learn English (and deal with American culture) due to the U.S.’s presence during the war and now turnabout is fair play. He made history by winning the Best Picture award for his film Parasite in 2020. It was a great awards year – Scarlett Johansson lost both(!) awards she was nominated for – and his win such an upset that soon-to-be-convicted former president Trump had to whine about it in his particularly moronic and racist way by saying:

“How bad were the Academy Awards this year? Did you see? And the winner is a movie from South Korea. What the hell was that all about? We’ve got enough problems with South Korea, with trade. On top of it, they give them the best movie of the year? Was it good? I don’t know. Let’s get ‘Gone With the Wind.’ Can we get, like, ‘Gone With the Wind’ back, please?”

To which the Democratic National Convention replied to on Twitter:

“Parasite is a foreign movie about how oblivious the ultrarich are about the struggles of the working class, and it requires two hours of reading subtitles. Of course Trump hates it.”

Their response is a sweet song to a film fan’s ears and echoed what Bong had famously said earlier:

“Once you overcome the 1-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.”

As an old-school film student, I appreciate the efforts taken to recognize a director’s intent include viewing and hearing the film as they wish it presented. Not knowing the language requires some audiences to rely on subtitles; however, we all know that inevitably something is lost in translation. The loss can be because of the imprecision of matching words and their meanings across different cultures, time constraints (what can be said pithily in one language may require more verbiage in translation, so there is usually a trade-off made between accuracy and length), and translator error.

Before the brouhaha with Parasite happened, Bong had released his second (mostly) English-language film after Snowpiercer through Netflix. It was about a genetically modified super pig (the title character Okja), animal activism, and the struggle between American capitalism and the Korean love of nature. It was a grab bag of styles, from over-the-top Netflix ridiculousness (Jake Gyllenhall’s washed-up Steve Irwin character), to the most charming and bucolic CGI reveries of Okja and her young tender Mija at home in Korea, to the most heart-wrenching display of the cruelties of animal testing and industrial farming. I would describe it as Charlotte’s Web meets Schindler’s List. Oh, and it has TWO Tilda Swinton characters. Two.

The plot is basically that a huge agribusiness company modeled after Monsanto (here barely disguised as the renamed Mirando Corporation) and run by the two Tildas has genetically modified some pigs, lied about their origins to pass them off as magical but natural mutations, and farmed out over two dozen super piglets to farmers around the world to raise. The goal for the company is widespread adoption of this new and cheaper meat source; however, when Okja is declared the winner and shipped to NYC, her best friend and handler Mija goes on an all out rescue mission. Along the way Mija is met and recruited by Paul Dano and his crew who represent the real world organization the Animal Liberation Front. Tears and laughter and thrills follow in rapid order up until the film’s powerful climax and amusing post-credits scene.

Bong Joon-ho is one of my favorite directors in any language and, in spite of the trivial made-for-Netflix feel of some it, delivers another cinematic wonder. Okja’s many strengths include:

> Darius Khondji’s (Se7en, Delicatessen, Uncut Gems, and Bong’s next film Mickey 17) exceptioal cinematography that moves effortlessly from the expected glorious wide shots of Korean wilderness that Bong often employs, to the busy streets of NYC, to Mirando’s gloomy industrial farm in Paramus, with assurance and style

> some amazing performances (I was particularly impressed by Paul Dano’s) that works to tie this sprawling ensemble effort together and shows Bong directing at a masterful level

> another killer soundtrack by Jung Jae-il (Parasite, Squid Games) that supports but never intrudes. I get bitchy when the composer vomits their sonic spew all over a film in a self-congratulatory way, trying to distract from sometimes weak narratives with blaring anthems, so Jung’s soundtracks have been a consistent and subtle joy so far

> Bong’s playful references to his earlier films like The Host (Mija’s head in Okja’s mouth, the twist at the end, etc.), Memories of Murder (the sheerly nighttime industrial farm shots, often from a high angle or directly above, that constant feeling of dread that suffuses every frame of those scenes) and Mother (characters in hiding, glorious Korean nature panoramas, surprising and brief moments of violence)

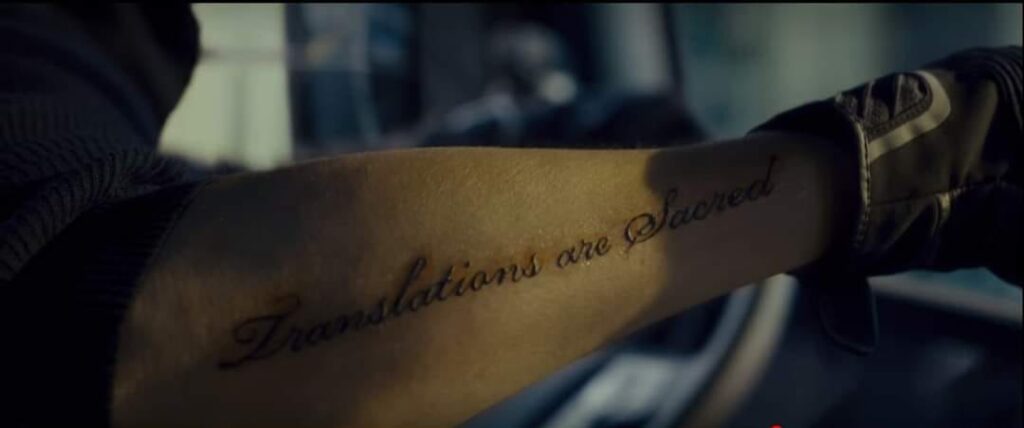

Central to the plot is a scene where the ALF tries to recruit Mija and seeks her permission to use Okja to infiltrate Mirando’s secret testing labs. Steve Yeun is tasked with translating but, like some of his fellow liberators, is desperate to carry out the mission at all costs and purposely mistranslates Mija when she says she wants to go home with Okja and not send her to the lab. The deception works and the horrors visited upon our dear porcine protagonist and hard to witness. Needless to say, when the truth is revealed, the shit hits the fan. As he pummels Yeun, Paul Dano reiterates that “Translation is sacred.”

Perhaps knowing he was dealing with a wider and more obtuse American market, Bong makes the point more cheekily a second time. Per IMDb:

“There is a mistranslation on the English subtitles when K played by Steven Yeun is about to jump out of the truck. According to the subtitles, his parting words to Mija are “Mija! Try learning English. It opens new doors!” What he actually says is “Mija! Also, my name is Koo Soon-bum.” It’s a flagrant mistranslation – but one that would only be apparent to those who can speak both languages. Moreover, the mistranslation is a clever subversion of the supremacy of English. The subtitle is a command to learn English – something that every Korean student has heard throughout her life – but to actually understand what K is saying, you would have to know Korean. There’s an added layer of comedy to the name itself, which has the whiff of the old country about it: “Koo Soon-bum” is sort of like a white man saying his name is “Buford Attaway.” As Yeun said in an interview, “When he says ‘Koo Soon-bum,’ it’s funny to you if you’re Korean, because that’s a dumb name. There’s no way to translate that. That’s like, the comedy drop-off, the chasm between countries.”

Frank Zappa said “You can’t be a real country unless you have a beer and an airline. It helps if you have some kind of a football team, or some nuclear weapons, but at the very least you need a beer.” To that I would suggest they also need a film industry. If don’t already know their world of flavors, I firmly believe you’ll love the world’s cinema as much as its cuisine. It’s just a matter of climbing that tiny wall and tasting the deliciousness on the other side.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.